It was a clear skied Saturday morning in Clairemont, San Diego when I arrived at Lucas Almassy’s childhood home, parking just across the street from where his Swiss mother, Austrian father, and 1 year old pup stood waving at me from their home outside my window. I was pleased to find that they’d been waiting for me, or at least convinced myself that they were, so I could be assured that I was indeed in the right place.

After exiting my vehicle, I introduced myself and they did the same. Their dog, a Border Collie/Pointer mix, jumped and panted gleefully at me, happy to meet someone new. I had a pleasant chat with the Almassys about my upbringing as it was our first time meeting before realizing I should probably call Lucas and tell him that I was here, when just then he exited the garage door and greeted me to welcome me into his home.

*

Lucas is an architect, designer, and polymath in the truest sense. If anybody reminds me of the greatest polymath to walk the earth—Leonardo da Vinci— the first person to come to mind, easily would be the late and great Virgil Abloh. But if I was to select an individual whom I knew personally, it would be Lucas.

Lucas and I had been well acquainted in high school through our affinity for the fine arts and his inclusion in a 2016 Gnashing Art Show I’d co-curated at the late La Bodega Gallery in Chicano Park. It wasn’t until I traveled to San Francisco to visit another friend of mine, James Sud, Lucas’ then roommate at UC Berkeley, that Lucas and I truly connected. It seemed he and I needed to reach some new level of maturity and gain some life experience before we could grasp the creative obsessions we shared.

Lucas holds no preference towards minimalism in contrast to profligate design, a testament, I must say, I wholeheartedly agree with. I take his perspective originates from how he grew up in a simply furnished suburban home with knickknacks ornamenting its spaces. And it was its very décor providing it the homey feeling I experienced upon entrance. From the cluttered woodshop in the garage to his father’s slightly scuffed 650cc BMW, the pool table and piano in the living room to Lucas’ personal ceiling meeting bookshelf filled to bursting, Lucas grew up in a normal, collectively developed home that must have shaped his design opinions.

During college and at the peak of the pandemic he explained that he’d buy and read books vigorously with the hopes of some change to his life coming about through them. “Every couple of days I’ll be like, ‘This book is going to change my life, I’m going to buy it.’ And often it does,” he told me. “What percentage of these books have you read?” I asked him. “It’d be easier to tell you which books I haven’t read,” he replied.

As is the case with every rendezvous between Lucas and I, an exchange of literature was bound to take place. Reaching towards the bookshelf, he pulled a book which he hadn’t read yet titled, Amerika, by none other than Franz Kafka. I had recently breezed through Metamorphoses and Other Short Stories, yet I don’t think Lucas had known of my affinity for Kafka’s works, not to mention the alternative short story version of Amerika, titled, “The Stoker,” being one of my favorite shorts in the collection. Lucas is a kind soul to say the least, always giving, always lending an ear, always putting his best foot forward to assist in the creation of beauty and new ideas. His habit of book giving was basically a tradition at this point, and if the book wasn’t for me, then a friend, and if not for a friend, then a stranger. Someone was always bound to be gifted.

I stowed the book in my messenger bag to then reveal the gift I had brought for him: A Guide to Architecture in Southern California, a glove compartment book published by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1965. The 5x6 inch book catalogues recognized architectural sites andhomes all over the So-Cal region with names and addresses for readers to visit, admire, or critique whenever they pleased. Lucas and I intended on spending the day together with the sole intention to talk art, design, and visit an architectural site or two, so I thought it only suitable.

I received a tour of Lucas’ room, where a large piece comprised of a bird’s eye view overlooking Clairemont resided on the wall immediately to the left of its entrance. In the distance of the landscape, was an empty lot where he was creating his own drawing of a nonexistent building, something similar to his futurist explorations, only on a much larger scale.

We exited the room, walking out to the pool in his backyard as I wielded my camera to shoot photos of him. He was relaying to me a reoccurring dream he had of an architectural phenomenon playing out behind his family home. In the dream, he walks into his backyard atop the brick-colored tiles which create a path towards the pool. Only the tiles in the dream extend out and over the pool into a garden façade where a multiplex stands, and an entire community of people reside, a sight he recounts as surreal and fulfilling.

Lucas talks a lot about community. In fact, many architects are hyper-focused on it. I find the communal importance of architectural design to be my main attraction to the practice as a community-oriented artist and individual. The attention designers like Lucas pay towards bringing people together—to the extent in which they dream of erecting a multiplex within their own backyard—only reassures the importance of the interdisciplinary conversations I remain adamant on having.

How to change the world is a question that comes up a lot between Lucas and myself. What do we want to change? Why is change important? What direction are we going in regard to architecture and community? Our answers to this question can and do go on for hours at a time, but today, when I ask him what his goal is with his work, his response is simple, and profound: “To make buildings that make you feel at home.”

To feel at home is a cliché-ridden experience that is also extremely honest. “Home is where the heart is”—true indeed. But Lucas’ ideas further explore that notion and implement the relocation of that feeling of home into other spaces. He may wonder, for example, what happens when a park feels like home? A storefront? A deli? A bookstore in the middle of the desert? What does it mean to enter a space and say, “I can live here”?

How often is that found, if ever?

Our talks of home and tranquil spaces reminded me of a renowned architectural site — John Pawson’s Contemplation Chamber, a space lined with black brick and a single grand corridor, designed for an individual purpose which can be defined by a quote engraved in the floor by Pascal: “All men’s miseries derive from not being able to sit in a quiet room alone.”

Perhaps it is that mankind needs this form of design, Lucas and I decide, as we walked around his pool in observance of the reverberating chlorine blue. Instead of creating communal meditation rooms on college campuses and in workplaces, we should place spaces designated for individual contemplation every few blocks. Allow people to step into a space and sit with their thoughts and feelings, have a room to ruminate in, lit by natural light or the evening moon. It seems humans need space to breathe, and Lucas initiates that maybe everyone, not just architects and thinkers like us, but everybody, takes part in a global mindset that we all have this instinct of what would make a better world.

Lucas and I left his family home and began driving down to Swish Projects in North Park where we had an appointment for Esther Wang’s new solo show, All Over In Place. We also had plans to meet up with another architect friend of mine, Jean Raymond, a designer from Côte d’Ivoire and an architecture student at The New School in Downtown San Diego.

As we cruised south on the 805, overlooking the now leveled Qualcomm Stadium, Lucas discussed his difficult relationship with technology and technological advancement. “My instinct these days,” he began, “is that I am very anti-technology. Idealistically, that is. But on a day-to-day basis, we’re driving cars, texting, and doing these things that aren’t immediately necessary.” Despite the purpose of these technologies being to connect people, there remains a massive disconnect which keeps us as people desperate for somebody to break the ice. After all, we sit inside our box shaped vehicles, remain face first in our phones, with public transit forever being a privilege harshly restricted from Americans, especially in SoCal. Public transit is one of Lucas’ favorite things, specifically for the element of communication it could bring about. “There’s nothing cooler in the world than to talk to a stranger,” Lucas riffs, “not smoking, not drinking, not buying a cool car, plus its free!”

He then tells me an anecdote of a recent day at the beach.

There was a woman he was talking to while surfing with whom he’d established a great connection. They talked for over 20 minutes while drifting into the ocean hundreds of feet south at La Jolla Shores to not even catch a wave. They enjoyed their conversation, felt great about the connection they made and the things they talked about, all to eventually go separate ways afterwards. “I prefer that nobody asks for social media after meeting. Just let that person go,” Lucas tells me. “It feels more genuine, because you didn’t get anything out of it.” Not a follower or potential client, collaborator or potential partner, nothing except a beautiful and valuable social interaction, something that most art and design is constantly yearning for.

Another thing Lucas had been thinking about was his paradoxical relationship with architecture and nature. “Even though I am an architect that designs buildings, I still think that the most comfortable place to be is sitting at a park under a tree. In fact, my brother and I were talking about Future the other day, about how his name is such a great name. And we thought about how he was able to just steal a word and make it his own. We decided we’d do the same. So, I decided that my name is Park,” Lucas told me.

Just as I learned of Park’s new name change, we’d arrived at the gallery, found a parking spot, and began walking over to see the show.

*

Perusing Esther’s paintings felt like a stream of consciousness personified. The works were abstract while simultaneously far from it. In fact, they read to be coherent despite their clearly sporadic nature, maybe even linear in terms of storytelling ability. However, the obvious layers, opacities, and merging figures implied some sense of blockage, breaks, and a sense of picking up where one left off, only each time with an altered viewpoint. One may see the same faces, but from various perspectives in the same form. It reminded me of a practice of Leonardo da Vinci to always view his subjects from at least three different perspectives. Only in Esther’s case, those perspectives seemed endless.

Lucas discussed process with Esther as I followed their conversation. He was enamored by her pieces, at first spending a considerable amount of time browsing and standing before each piece deep in thought and scrutiny of the brush strokes, excessive layers, and attention to detail Esther naturally produced. He spoke to her of how he could tell the pieces were carefully planned, worked, and reworked many a time despite their apparent abstraction, and Esther confirmed Lucas’ observations to be true. Externally, it seemed to be a telepathic connection between painters taking place before me. After all, Lucas was an artist and painter before he was an architect, and with his grandfather too being a notable painter, abstract interpretation was not something unfamiliar to him.

Edwin, John, and Bob sifted in and out of the room doing their duties while JR, Esther and I engaged with the show going back and forth on various topics. We discussed the confliction between societal norms and living a life of unorthodoxy, to Esther’s upbringing as a voraciously curious child that still asks endless questions to anyone that she holds a conversation with. Lucas, however, stood in the corner partaking in a quiet conversation with Esther’s father who also attended the show. They seemed to be deep in conversation, and from what I know, were discussing life and architecture.

I found Lucas’ tendency to enjoy conversations with strangers to be true, as Esther’s father was a stranger to Lucas. As I glanced over while they conversed in the gallery corner, I saw them sharing laughs, concerned nods, and delicate ideas.

When we finally reconvened, all of us spent a substantial amount of time in front of the gallery discussing art, literature, and being put onto game by Edwin, reminding us of the importance of working on our craft and just doing the work. It was a classic day at Swish, and everyone left feeling a bit more inspired than when we entered.

*

JR, Lucas, and I headed to Pokez downtown for lunch. JR was headed to campus soon to work on a project, so I’d drop him off after we stopped to eat just a few blocks away. As he discussed the elements of said project from the backseat with Lucas, deep in architectural discourse, Lucas stopped and asked, “What was your name again?”

“Jean Raymond,” JR replied with a distinct French accent, “Although my friends here call me JR.”

“You speak French?” Lucas asked him.

“Unfortunately, it is my first language.” JR jokingly replied.

“Très bien. Moi Aussi! C'est pas ma première langue. Ma mère n’est pas français, mais de la Suisse,” Lucas replied.

I’d watched enough Rohmer to get a semblance of what they were saying, though it was a clear reminder that Lucas remains the renaissance man I’d known him to be! I knew his parents were European, though I didn’t know of his ability to speak French. JR found that plot twist rather exciting as well.

As we drove into downtown off the 94 freeway, Lucas pointed to a parking lot and said, “I met Henri in that parking lot.” I looked over and noticed, it was just an empty lot. There was no restaurant, no shop, and no notable building connected to it.

“It’s always niggas in a parking lot,” I said aloud. “No matter where you go, niggas will be posted.” JR laughed in agreement.

“That’s where it all starts,” Lucas added. “A parking lot is like the manifestation of freedom. You can show up and do whatever you want. No one is going to question what you are doing there because no one is from the parking lot,” and he couldn’t be more right.

We arrived at Pokez, parking just down the block from the restaurant. As JR took a phone call I shot some photos of Lucas, then JR, then both of them. We entered the restaurant I always came to as a young grimy skater kid in high school, then as the artsy college kid showing artist friends my city. The restaurant was a bit dark in ambience, full of art, stickers on walls, bright reds and greens, and solid wooden booths. Lucas ordered a California Burrito, I ordered a few shrimp tacos, and a chorizo burrito for JR.

When we finally got comfortable, Lucas placed a binder before us on the table. In it were all his Futurist Explorations drawings. It was a bit surreal to see them in person, kind of like the first time viewing a Kandinsky or Basquiat when one had only ever seen them in pictures. So, we immediately began sifting through and discussed them one by one.

*

“WHY LIVE IN TALL BUILDINGS ... SO WE DON’T WASTE PRECIOUS SPACE,” the first one reads.

The drawing is of a solitary high rise which I am immediately fixated on. Surrounded by luscious grasses and brush, the building begins at the bottom floor consisting of a parking structure. A sleek bridge entering the frame from the right leads directly into the structure – one way in, one way out – reinforcing its individuality. Beneath the bridge is farmland and space for gardening and recreation, and as one transcends the building, we find space for population. The very structure consists of office spaces for rent, so I imagine this is a place where residents in the building both work and live, and if not, use it as a chance to meet new people who work in and frequent the complex. Above that floor are the public services. It doesn’t go into detail what kind of public services although I would imagine it possesses grocery stores, pharmacies, a leasing office, urgent care, and necessities of the like. As it is not the most densely populated area, its being so far and separated from the city, the building looks to be mostly designed for accessibility and its immediate community.

We then ascend to the largest section of the high rise – its apartments. Personally, I cannot fathom living somewhere like this. Looking out over the lagoon and desert terrains, not to mention the gliders descending from the glider port just above the apartments, the experience of residing somewhere as such feels rather surreal and dream-like. Sentiments as such prove to show the difference between mere developers of commercial buildings, and architects who design space. The high rise seems more fiction than reality, despite its inherent possibility to comfortably exist. All it takes is someone with the idea and will to manifest it.

“A big part of making spaces more comfortable is varying the sizes of trees and greenery,” Lucas explained to me. Looking at his high rise, you see the varying sizes and altitudes of greenery surrounding the structure, creating this expanse of space which provides a sense of breathing room, not to mention the beautiful view one would be able to find looking out from just about any floor or locale in vicinity to a window in the building. It is then when the question occurred to me, why it is that a structure like this one Lucas drew up felt and perceived to be futuristic?

I posed this question to both Lucas and JR and JR began to explain how, in the past, what ‘futuristic’ in architecture constituted was something like Neo-Tokyo in Katsurhiro Otomo’s Akira or what contemporary Manhattan, New York looks and feels like today. An amalgamation of massive buildings and high rises functionally situated in a densely populated environment near the water. “Most tall buildings have tall buildings around them. This one doesn’t,” Lucas explained. “This is the San Luis reservoir, the densest thing you could imagine, with no surrounding density at all.”

Since Manhattan already exists, that idea of compact high rises is no longer futuristic, and it is because of this that Lucas, JR, and I reach the consensus that futurism is variable. What the future feels like changes based on today’s norms and breakthroughs. Virtual realities are no longer futuristic as they are now a present reality, albeit a concerning one that we must learn to accept and live with. Therefore, futurist technology is always redefining itself as we continue to create.

We talked for a while longer, I finished my tacos, JR his burrito, and Lucas wrapped his in a bag to-go. We saw JR off to campus before Lucas and I departed on our final side mission of the day. The afternoon was still pristine even though the sun was going to set soon.

*

One of my first introductions to architecture was through an essay Lucas wrote in college titled: A Translation from the Literary to the Architectural. The piece was about exactly that, reading architecture and buildings as one would read a text, and in this essay his text was none other than our local and renowned Salk Institute of Biological Studies by Louis I. Kahn.

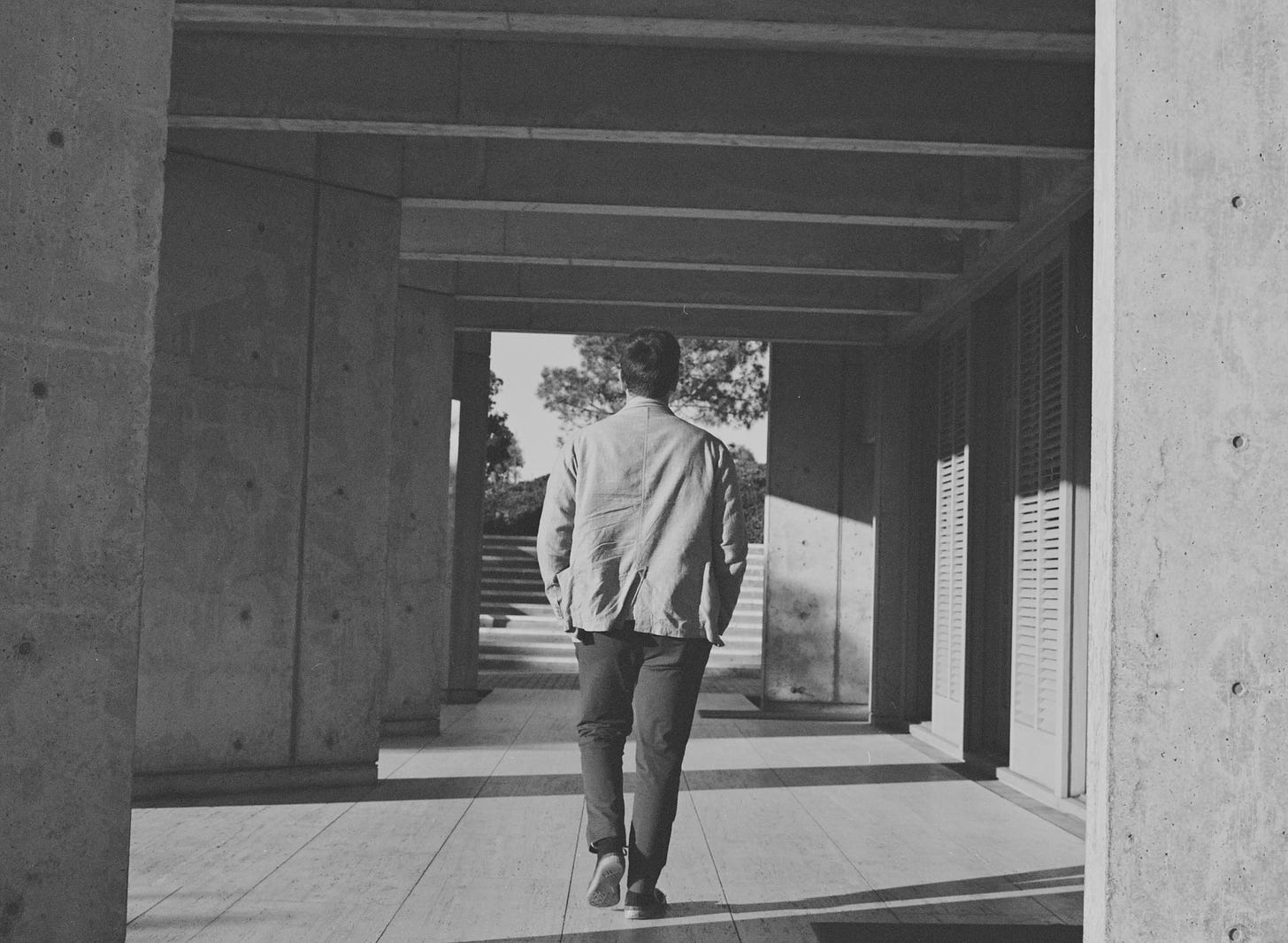

We made the short drive north as I was craving another visit to this wonder of the world. And as we walked toward the entrance, we were disappointed to find it had been closed to the public. A security guard informed us that, “They cannot afford to get any of their scientists sick with covid.” So, Lucas and I continued on the path outside the building, mostly in silence as we’d extracted just about every idea and conversation we could have that day, and this time was simply a time for observance and experience of this incredible structure.

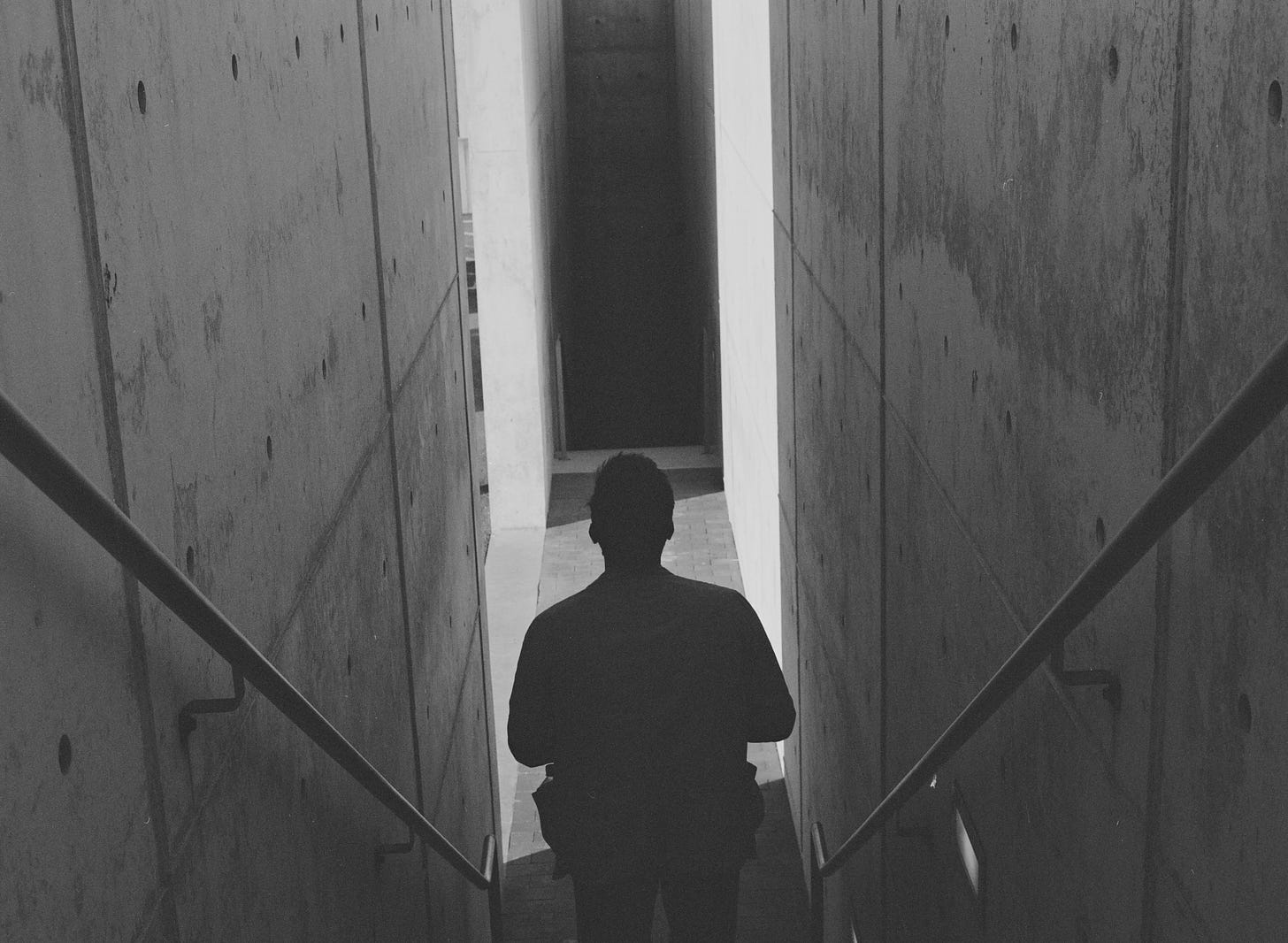

Walking to the back, with the security guard out of sight, I very much wanted to capture a few photos of the site. Being that I had multiple cameras, and the security guard was bound to kick us out as soon as we stepped foot onto the property, I gave Lucas one of my cameras and asked him to shoot some photos for me as well. It would be a quick operation. Get in. Get out. I was armed with my medium format 120mm Bronica ETRS, and Lucas, my 35mm Canon T50, and so we loaded, readied, and stormed in.

Security must have been lounging somewhere, as we were left unbothered for some time. It didn't turn out to be a quick operation at all. Overlooking the Pacific Ocean, with this brutalist, grandiose structure standing before you, commandeering your attention and admiration, you couldn’t help but just pause every so often to take it all in. I could see that Lucas really loved this place. He hardly said a word as he paced the courtyard with his hands in his pockets, and the camera around his neck. It was as if some nostalgia was associated with this place, some feeling of saudade, a quietude and contentment. And that was when it hit me why Lucas loved this place – it felt like home. In fact, it was home: San Diego, La Jolla Shores, The Pacific Ocean. All places he and I were too familiar with. But it was this structure that reinforced that notion of “I can live here,” over and over again.

*As featured in Issue No. 1 of Deixis Journal